The Lazy Why: What We're Getting Wrong About Hybrid Work and the Post-Pandemic Office

There appears to be a contradiction surrounding hybrid work. In private conversations, almost everyone expresses longing for the camaraderie and personal interactions of working in-person. However, when asked in surveys, people consistently show an overwhelming preference for remote work. This contradiction leaves employers in a difficult situation: alienate a chunk of your employees by forcing one way or another, or opt for a safe middle-ground in hybrid work that doesn’t satisfy anyone. Or, dig deeper to understand how both sides of the contradiction can be correct.

Splitting the difference

Good negotiators know that “splitting the difference” is the worst possible outcome to any negotiation – all parties get a watered-down version of what they really wanted and no one is happy. This is what’s happening in the hybrid work discussion.

Remote-preferring people get to stay at home but suffer the annoyances of poor remote work processes and weekly commutes into a deserted office where they have no desk. Office-preferring people sit in those deserted offices, still on Zoom calls, and only occasional face-to-face work sessions with people.

The best negotiations start from a deeper understanding of the parties involved. Only in understanding the goals and problems of all sides, can you find terms everyone is excited about. As leases come up for renewal over the next several post-pandemic years, businesses are being forced to think about what their offices look like going forward, and if they only hear their employees literally, they risk demotivating all of them.

Don’t listen to what people say

David Ogilvy, the founder of the legnedary Ogilvy & Mather ad agency, was not a fan of market research, saying:

“People don’t think what they feel, they don’t say what they think, and they don’t do what they say.”

You might remember a similar Steve Jobs quote about focus groups:

“A lot of times people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

They were communicating an uncomfortable truth: we don’t really know why we do things, despite all our rationalizations.

(For the record, I’m not suggesting you shouldn’t talk to people, just that you shouldn’t take their answers at face-value. Listen to what they say, but try to understand what they feel.

Marchetti’s Constant

Take for example, the common answer you hear when asking people why they don’t want to come to the office: “Commuting is a waste of time.” If you take that as true, you might start thinking of ways to reduce commute time, but is time the actual issue?

David Metz would tell you it’s not. Metz was the Chief Scientist at the UK Department of Transport and he discovered that when commute times were reduced (usually with very expensive infrastructure projects), people didn’t bank the saved time for other activities, they simply moved farther away. They found better jobs in more distant locations, or took advantage of cheaper housing farther out of the city, and still commuted the same amount of time.

For decades of transportation planning, the assumption was that people desired faster modes of transportation to save time. In reality, it was never about time.

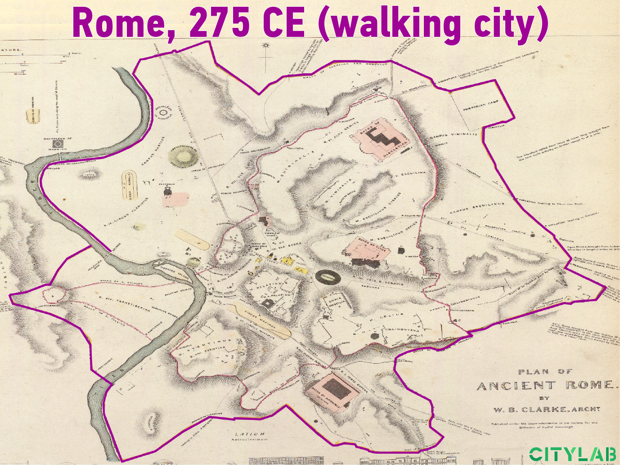

(This fascinating phenomenon is called Marchetti’s Constant btw, named after the Italian physicist who discovered in 1994 that cities have been shaped since ancient times by our ingrained willingness as a species to travel a total of 1 hour per day, regardless of distance or mode of travel.)

Ancient Rome was exactly 1 hour from the edge to the center and back.

Image source: David Rumsey Map Collection courtesy Stanford University Libraries, CC-BY-NC-SA; image credit: David Montgomery/CityLab

Commute-regret

One framing of the hybrid work question is the idea of commute-regret. I came across the term in a Microsoft article about the changing workplace:

"To make the office worth the commute, employees need a good reason—more than simply ‘because I said so.’ But it’s hard to know when colleagues are coming in, and too often, employees have commute-regret: the unique frustration of making the commute just to be alone in the office, doing work they could have done from home."

I experiences this term first-hand when visiting an old workplace of mine. In this office that once held 500 people, there were now only 30-50 people on any given day – a waste land. If you knocked over some furniture and scattered some dust, you’d think it was a set from The Last of Us. Even a mere 5-minute walk wouldn’t be worth the commute to a place like this.

What’s useful about regret as a framing is that it’s a feeling, and feelings are more likely to bring us closer to the solutions that resonate with people.

There are many other framings, and to be honest I haven’t thought about this too much so I don’t claim to have the answers. What I am advocating though, is for asking more questions to open up the possibilities.

The future of office work?

Beware The Lazy Why

“The Lazy Why” is any satisfactory, rational answer to a question. People don’t like commuting because it’s a waste of time is a lazy why.

We’re taught in school that every question has an answer, but only in math and science is this true. When there are people involved, there are always many answers.

Lazy whys practically guarantee you’ll design the wrong solution. They make so much sense that we miss the emotion that actually drives the majority of people’s decision-making. "The heart has its reasons, which reason does not know." - Blaise Pascal

To wrap up, we need to dig deeper into people’s feelings and experiences around work post-pandemic. This means asking more questions and being open to the idea that there might be more than one "right" answer. In this way we can design new ways of working that are exciting, rather than defaulting to a watered-down compromise that nobody actually wants.

🥑 Subscribe here to get posts automatically.